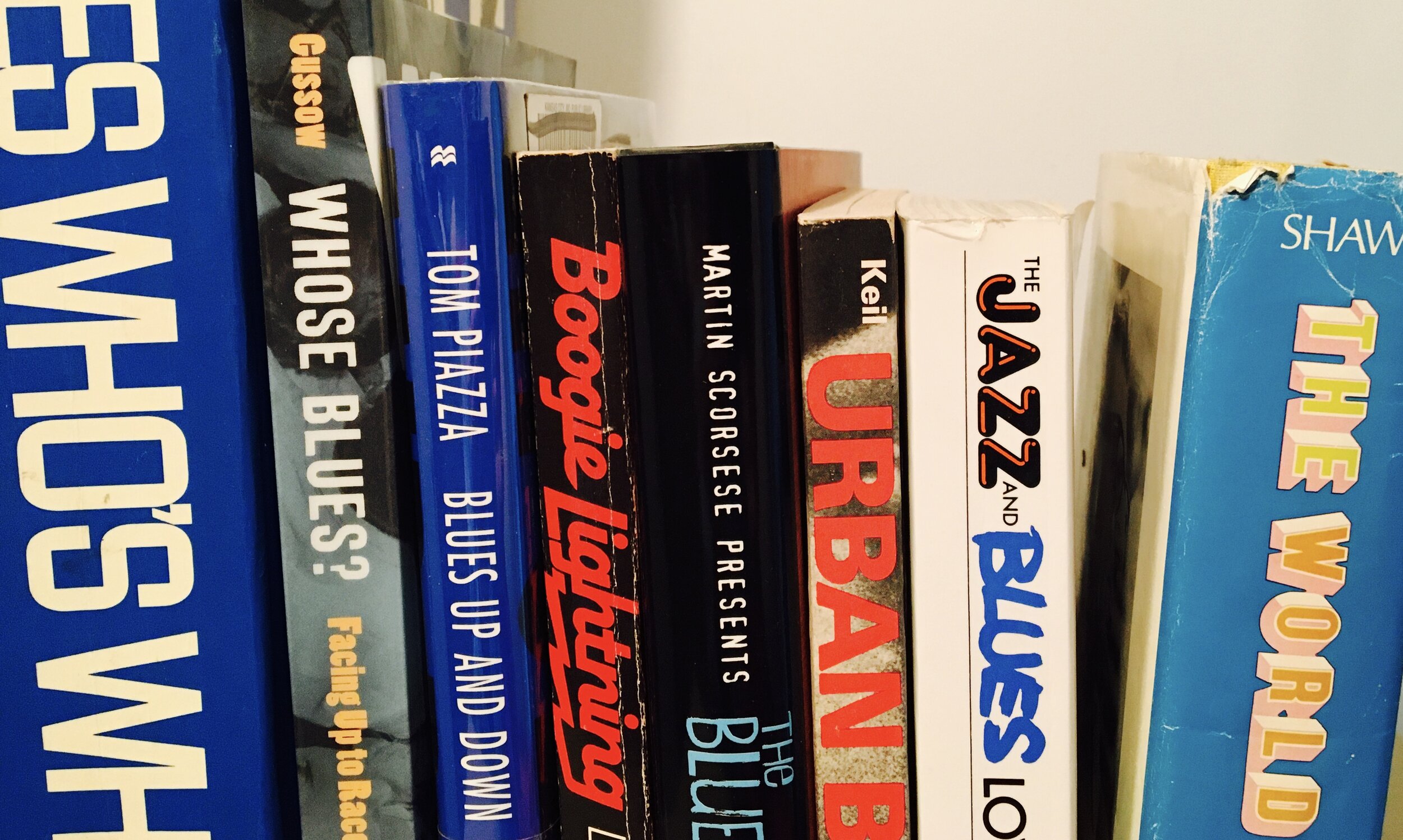

Original image by There Stands the Glass.

Prior to reading Whose Blues? Facing Up to Race and the Future of the Music, I wouldn’t have given a second thought to my enjoyment of Chris Cain’s new album Raisin' Cain. The journeyman revives the classic sound of B.B. King with uncanny accuracy. Yet Adam Gussaw’s searing examination of the racial aspect of the blues permanently annihilated my capacity to nonchalantly indulge in such simple pleasures.

The implications of a white American- no matter how talented or well-intentioned- reworking a black art form inextricably linked to oppression of African Americans is fraught with complication. While I was initially resistant to Gussaw’s assertions, his profound personal experiences and exacting scholarship convinced me that unmindful appreciation of blues power is morally irresponsible.

Gussaw lays out cases for the competing claims about the music. The proprietary “black bluesist” camp is diametrically opposed to the historically agnostic and ostensibly colorblind “blues universalists.” The extensive research Gussaw references makes it clear neither side has it entirely right. Whites encouraged and contributed to the development of the music from the onset.

In addition to discrediting the commonly held notion that the blues was forged on Mississippi plantations, Gussow mocks the rockist mythology that elevated Robert Johnson from a virtual unknown into an iconic figure. Obviously, the cultural appropriation he documents recurred in additional forms including jazz, rock, soul and hip-hop.

While he generally treads lightly, Gussaw sometimes can’t hold back. He openly mocks the tone-deaf culture of blues societies and is unable to hide his disdain for white blues artists ranging from Janis Joplin to Marcia Ball. He suggests the likes of Aki Kumar and Komson represent the best hope for a meaningful blues revival.

More than a third of Whose Blues is dedicated to literary criticism. Gussaw’s extensive analysis of the writings of W.C. Handy, Langston Hughes, Zora Neale Hurston, Ralph Ellison, Richard Wright and August Wilson is a surprising but welcome tangent. Grateful for Gussaw’s insights, I’ve since picked up a Library of America anthology of Hurston’s work.

Gussaw would almost certainly be pleased by my interest in Hurston, but he’d surely find fault in my inability to adjust my sincere affection for the music made by white boogie-crazed blooze-rock stalwarts in Kansas City. Most of these artists are so far removed from the blues tradition that reflective self-authentication would be pointless. Should Gussaw analyze this thriving subgenre, I suggest he title the book What Blues?: The Whitewashing of America’s Musical Roots.