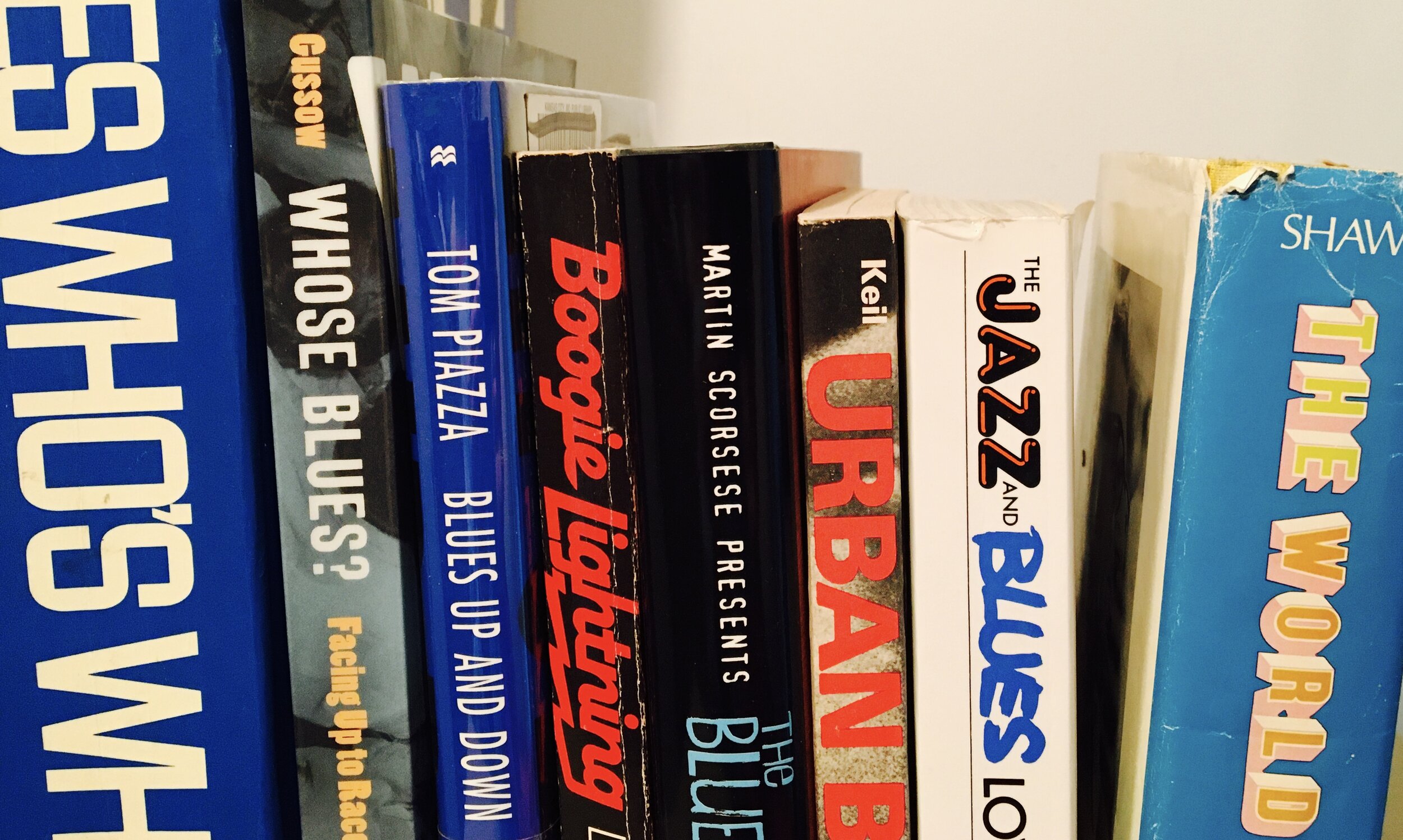

Original image by There Stands the Glass.

Blaring my favorite music through open windows while driving a freshly washed car is enormously pleasurable. After spending a good part of a recent trip sitting on the front porch of a home in Hamtramck, a densely populated Muslim-majority city adjacent to Detroit, Michigan, I decided to permanently curb the selfish impulse.

It’s not merely inconsiderate. I now recognize the practice is a mild form of societal violence. The imposition of one’s taste in music on others is part of the point, but I hadn’t previously considered that I might be insulting the cultural and religious sensibilities of blameless innocents. Witnessing the little girls of Yemeni and Cameroonian descent who were my temporary neighbors being repeatedly subjected to lurid raps booming from passing vehicles was infuriating.

I’m hedging my bets even though I now feel terrible about each of the times I may have offended passersby with similarly intrusive behavior. I listened to the invaluable reissue of my favorite Sun Ra album in a remote corner of a commercial parking lot yesterday. The two puzzled shoppers who inexplicably parked near me were treated to my theme song.

---

I reviewed Robert Castillo’s Music for Art Show at Plastic Sax.

---

Howard Mandel’s remembrance of Bob Koester rings true. I had a few prickly interactions with the late Chicago legend in the 1990s.